There are few German painters who have had as long and distinguished a career as Max Beckmann, and fewer still who have been able to sustain the consistent level of excellence he maintained throughout his career. Some, such as August Macke and Franz Marc, had their lives cut tragically short while serving in war, while others, such as Otto Dix, George Grosz, and Christian Schad, were unable to regain their creative edge following Nazi persecution.

Beckmann not only survived such misfortunes but excelled in spite of them. Between 1905 and 1950, he created more than eight hundred paintings and produced hundreds of prints and drawings, a phenomenal output under any circumstances, and even more considerable when one realizes the challenges that faced him during the height of his career. Persecuted by the Nazis, he was forced to flee his homeland and work in relative isolation while the war turned Europe upside down.

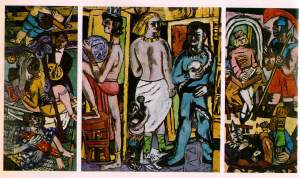

“A painter’s painter, he eschewed identification with a particular school or style. His oeuvre is a celebration of painting’s grand traditions – the still life, the portrait, history painting, and allegorical and mythological subjects – articulated in a visual style that has often been described as Expressionist. But while his frenetic brushwork and highly complex, metaphysical iconography have much in common with German Expressionism, Beckmann’s paintings never succumbed to the Modernist tendency to render the world abstractly. In his 1938 lecture “On My Painting,” Beckmann explained: ‘I hardly need to abstract things, for each object is unreal enough already, so unreal that I can only make it real by means of painting.’…

“A painter’s painter, he eschewed identification with a particular school or style. His oeuvre is a celebration of painting’s grand traditions – the still life, the portrait, history painting, and allegorical and mythological subjects – articulated in a visual style that has often been described as Expressionist. But while his frenetic brushwork and highly complex, metaphysical iconography have much in common with German Expressionism, Beckmann’s paintings never succumbed to the Modernist tendency to render the world abstractly. In his 1938 lecture “On My Painting,” Beckmann explained: ‘I hardly need to abstract things, for each object is unreal enough already, so unreal that I can only make it real by means of painting.’…

“Beckmann was born in Leipzig in 1884, the youngest of three children. His father, a grain merchant, died when Beckmann was only ten years old. By the age of fifteen, after several years of boarding school and over his family’s objections, he decided that his destiny lay as a painter. After failing the entrance exam for the Königliche Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Dresden, Beckmann was accepted by the Grossherzogliche Sächsische Kunstschule in Weimar in 1900. The school provided him with an academic art education, whereby he learned to draw from antique sculpture as well as from live models. At school, he met Minna Tube, a fellow artist whom he married in 1906 and who gave birth to his only child, Peter.

“After completing his studies in 1903, Beckmann made the first of many trips to Paris, the city that to him represented the peak of artistic accomplishment. The political upheaval caused by two world wars, however, would prevent him from ever realizing his goal of permanently settling and pursuing his art there.

“After completing his studies in 1903, Beckmann made the first of many trips to Paris, the city that to him represented the peak of artistic accomplishment. The political upheaval caused by two world wars, however, would prevent him from ever realizing his goal of permanently settling and pursuing his art there.

“By 1906, Beckmann had become an accomplished painter. After moving to Berlin, he participated in exhibitions with the Berlin Secession, the predominant voice of Modern German painting at the time. Like the works by its senior members – Lovis Corinth, Max Liebermann, and Max Slevogt – Beckmann’s paintings from this period are characterized by the legacy of Impressionism, with landscapes and beach scenes rendered in stippled brushstrokes to evoke the play of light across forms. He was held in such high regard by his colleagues that, in 1910, he was elected to the executive board of the Secession, becoming the youngest member ever to achieve such a distinction. Preferring art making to policy making, however, he resigned the following year in order to devote himself full-time to painting.

“By 1906, Beckmann had become an accomplished painter. After moving to Berlin, he participated in exhibitions with the Berlin Secession, the predominant voice of Modern German painting at the time. Like the works by its senior members – Lovis Corinth, Max Liebermann, and Max Slevogt – Beckmann’s paintings from this period are characterized by the legacy of Impressionism, with landscapes and beach scenes rendered in stippled brushstrokes to evoke the play of light across forms. He was held in such high regard by his colleagues that, in 1910, he was elected to the executive board of the Secession, becoming the youngest member ever to achieve such a distinction. Preferring art making to policy making, however, he resigned the following year in order to devote himself full-time to painting.

“In the years leading up to World War I, Beckmann’s work evolved into grand compositions of religious and mythical subjects in the tradition of Eugène Delacroix, Peter Paul Rubens, and Rembrandt van Rijn.

“In the years leading up to World War I, Beckmann’s work evolved into grand compositions of religious and mythical subjects in the tradition of Eugène Delacroix, Peter Paul Rubens, and Rembrandt van Rijn.

The war interrupted his work, however, and after serving as a medical volunteer for a year, he suffered a breakdown and was discharged to Frankfurt in 1915 to recuperate. When he began to paint again in earnest in 1917, his style changed radically, assuming a Northern Gothic sensibility couched in a Modern idiom. His forms became more mannered and polished; his colors became more intense, and his rendering of space took on a vaguely Cubist orientation, with figures compressed into torturous settings and angular forms tilting precariously toward the picture plane. His works became a mosaic of contemporary social criticism and religious or mythical themes, and he increasingly used masked or costumed circus characters as allegorical figures, a practice that became a hallmark of his art.

“By the mid-1920s, Beckmann had become one of Germany’s foremost Modern painters. His work was hailed as a leading example of Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), a short-lived movement distinguished by the rejection of Expressionism and the revival of realism. Often cynical in its outlook, Neue Sachlichkeit moved away from the subjectivity of Expressionist emotion and chronicled the bourgeois excesses of Weimar culture with a frighteningly detached demeanor. While Beckmann certainly engaged in social criticism in his work during this period, he did so in a broader context than other artists associated with Neue Sachlichkeit, such as Dix and Grosz, continuing to confront metaphysical issues in his paintings.

“By the mid-1920s, Beckmann had become one of Germany’s foremost Modern painters. His work was hailed as a leading example of Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), a short-lived movement distinguished by the rejection of Expressionism and the revival of realism. Often cynical in its outlook, Neue Sachlichkeit moved away from the subjectivity of Expressionist emotion and chronicled the bourgeois excesses of Weimar culture with a frighteningly detached demeanor. While Beckmann certainly engaged in social criticism in his work during this period, he did so in a broader context than other artists associated with Neue Sachlichkeit, such as Dix and Grosz, continuing to confront metaphysical issues in his paintings.

“In 1925, Beckmann was appointed to teach at the Kunstgewerbeschule of the Städelsches Kunstinstitut in Frankfurt, a position he held until 1933. Also in 1925, he divorced Minna Tube and married Mathilde (Quappi) von Kaulbach, who became the subject of many of his important paintings. The following year, he had his first solo exhibition in the United States, at J. B. Neumann’s New Art Circle gallery in New York, thereby expanding his reputation in the international art community. With several distinguished publications devoted to his art already in circulation, Beckmann was accorded a large retrospective exhibition in 1928 at the Kunsthalle Mannheim, organized by its director, G. F. Hartlaub (the originator of the term Neue Sachlichkeit). That same year, Beckmann received one of the nation’s highest honors in the fine arts, and a gold medal from the city of Düsseldorf in recognition of his artistic achievements. In 1930, a permanent gallery for Beckmann’s art was established at the Städtische Galerie of the Städelsches Kunstinstitut. Two years later, he received further distinction when a room was dedicated in his honor at the Nationalgalerie in Berlin and ten major works by him were placed there on permanent display.

“In 1925, Beckmann was appointed to teach at the Kunstgewerbeschule of the Städelsches Kunstinstitut in Frankfurt, a position he held until 1933. Also in 1925, he divorced Minna Tube and married Mathilde (Quappi) von Kaulbach, who became the subject of many of his important paintings. The following year, he had his first solo exhibition in the United States, at J. B. Neumann’s New Art Circle gallery in New York, thereby expanding his reputation in the international art community. With several distinguished publications devoted to his art already in circulation, Beckmann was accorded a large retrospective exhibition in 1928 at the Kunsthalle Mannheim, organized by its director, G. F. Hartlaub (the originator of the term Neue Sachlichkeit). That same year, Beckmann received one of the nation’s highest honors in the fine arts, and a gold medal from the city of Düsseldorf in recognition of his artistic achievements. In 1930, a permanent gallery for Beckmann’s art was established at the Städtische Galerie of the Städelsches Kunstinstitut. Two years later, he received further distinction when a room was dedicated in his honor at the Nationalgalerie in Berlin and ten major works by him were placed there on permanent display.

“With Hitler’s appointment as chancellor in 1933, Beckmann’s good fortune, and that of German political and cultural life in general, abruptly declined. The Nazis viewed Modern art as socially and morally corrupt, and they began to purge Germany’s cultural institutions of everything they perceived to be weakening the fiber of the country’s heritage. Beckmann’s work, along with that of many artists held in high regard today, was suddenly labeled ‘degenerate.’

“With Hitler’s appointment as chancellor in 1933, Beckmann’s good fortune, and that of German political and cultural life in general, abruptly declined. The Nazis viewed Modern art as socially and morally corrupt, and they began to purge Germany’s cultural institutions of everything they perceived to be weakening the fiber of the country’s heritage. Beckmann’s work, along with that of many artists held in high regard today, was suddenly labeled ‘degenerate.’

“Art dealers who had supported Beckmann now shied away from him or left the country fearing Nazi persecution. Beckmann’s art was methodically removed from German museums, and by 1937, nearly six hundred of his works had been confiscated. That July, following Hitler’s radio broadcast at the opening of the infamous Degenerate Art exhibition – the Nazi propaganda exercise that definitively extinguished the avant-garde in Germany – Beckmann fled with his wife to live with her sister in Amsterdam, never to return again. It was an abrupt and humiliating transition for an artist who had been hailed only four years earlier as a national treasure.

“Art dealers who had supported Beckmann now shied away from him or left the country fearing Nazi persecution. Beckmann’s art was methodically removed from German museums, and by 1937, nearly six hundred of his works had been confiscated. That July, following Hitler’s radio broadcast at the opening of the infamous Degenerate Art exhibition – the Nazi propaganda exercise that definitively extinguished the avant-garde in Germany – Beckmann fled with his wife to live with her sister in Amsterdam, never to return again. It was an abrupt and humiliating transition for an artist who had been hailed only four years earlier as a national treasure.

“For the next ten years, Beckmann worked largely alone, except for the company of his wife and a few close friends, using a large tobacco storeroom as his studio. The outbreak of war in Europe confined him to Amsterdam, except for occasional sojourns to Paris or the Dutch countryside.

“For the next ten years, Beckmann worked largely alone, except for the company of his wife and a few close friends, using a large tobacco storeroom as his studio. The outbreak of war in Europe confined him to Amsterdam, except for occasional sojourns to Paris or the Dutch countryside.

“Beckmann’s diaries from these years are replete with accounts of his frequent visits to cabarets, carnivals, and the theater. On one level, these distractions offered temporary relief from the horrors of the war, the tragedies of which nonetheless found their way into his art. On another level, however, Beckmann regarded them as allegories of human existence. Thus, his paintings from these years – some of the most important works of his career – are abundant with subjects whose identity is both constructed and obscured by masquerade. Indeed, three of the triptychs, Akrobaten (Acrobats, 1939),Schauspieler (Actors, 1941-42), and Karneval (Carnival, 1942-43), make specific reference to these genres, offering grand theatricalizations of human tragedy rather than celebrating the lighthearted pleasure such spectacles usually elicit.

“Beckmann’s diaries from these years are replete with accounts of his frequent visits to cabarets, carnivals, and the theater. On one level, these distractions offered temporary relief from the horrors of the war, the tragedies of which nonetheless found their way into his art. On another level, however, Beckmann regarded them as allegories of human existence. Thus, his paintings from these years – some of the most important works of his career – are abundant with subjects whose identity is both constructed and obscured by masquerade. Indeed, three of the triptychs, Akrobaten (Acrobats, 1939),Schauspieler (Actors, 1941-42), and Karneval (Carnival, 1942-43), make specific reference to these genres, offering grand theatricalizations of human tragedy rather than celebrating the lighthearted pleasure such spectacles usually elicit.

“In the war’s aftermath, Beckmann immigrated to the United States, where he taught and painted during the last three years of his life. By this time, he had found widespread acceptance as a major force in twentieth-century art. When he died in December 1950, he had just finished Argonauten (The Argonauts, 1949-50), the ninth of the monumental triptychs that distinguish his mature career. His studio contained several unfinished canvases-including a tenth triptych – testifying to the boundless creative energy that he possessed in spite of his failing health.”

“In the war’s aftermath, Beckmann immigrated to the United States, where he taught and painted during the last three years of his life. By this time, he had found widespread acceptance as a major force in twentieth-century art. When he died in December 1950, he had just finished Argonauten (The Argonauts, 1949-50), the ninth of the monumental triptychs that distinguish his mature career. His studio contained several unfinished canvases-including a tenth triptych – testifying to the boundless creative energy that he possessed in spite of his failing health.”

– From Matthew Drutt, Introduction to the catalog, “Max Beckmann in Exile”